What Affects The Export Performance: A case study of Nafis Nakh Textile Company

Mahdi Beedel

Faculty of Administrative Sciences and Economics, Department of Accounting, University of Isfahan, Iran

Sasan Ghaffarifar

Department of Industrial Management, Qazvin Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qazvin, Iran

Mahmoud Mosafer

Department of Accounting, Abhar branch, Islamic Azad University, Abhar, Iran

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to examine what affects the export performance and the propensity to export. For this purpose, Nafis Nakh, as a successful and growth textile company in terms of export is chosen for investigation. The study analyses firm’s resources and capabilities in a ten year period from 2007 to 2017 using monthly time series data. Reviewing researches done in this field, different Intra Organizational and Extra organizational (environmental) factors were considered in order to formulate the research model.

Pearson Correlation Coefficient and Multiple Linear Regression Technique were used to test the hypotheses. With regards to firm specific factors which exert an influence on export performance, the results revealed that firm size, international experience, productivity, educational level of managers and innovation have significant positive effects on export performance. Furthermore, in the industry level analysis, exchange rate volatility and capital to labour ratio were found to be significantly and negatively related to a firm’s export participation and its export performance. Finally, we find no evidence that skilled labors, inflation rate, and domestic market growth have any significant relationship with export performance.

Keywords: Nafis Nakh Textile Co, Textile industry, Export performance, Firm-Level factors, Industry-Level factors.

1. Introduction

Access to foreign markets is a critical determinant of export performance. Here, the term “foreign market access” is seen as representing the foreign market potential of a country. Thus, increased attention has been given to the firm’s internationalization and foreign markets, and exporting has been recognized as the most common foreign entry among such internationalization alternatives (Fernandez et al., 2004). In general, there has been widespread improvement in foreign market access since the early 1980s, which matched to a large extent improvement in export performance (Adjasi, 2007; Abor, 2011).

Export performance exhibits a multidimensional structure, confirming the complex nature of the construct. Although simplicity and security will make companies prefer the domestic market to the foreign market but lack of sufficient opportunities in domestic markets and availability of suitable opportunities in foreign markets has led companies to try to allocate all or part of their sales to foreign markets.

Strong export performance is usually known as one of the important factors in driving a country’s economic growth, since exports can improve a firm’s production efficiency to overcome higher trade barriers and address different market tastes in competitive international markets (Amornkitvikai et al., 2012).

Due to the high political and economic costs placed on stable regimes as a result of sanctions, Western countries tend to put more pressure on vulnerable countries (Dizaji and Van Bergeijk, 2013). Iran has been affected by economic sanctions imposed by Western countries, especially the U.S. Since 2006 and with the development of the Iranian nuclear conflict, the United Nations has frequently imposed economic and financial sanctions against Iran.

As a result of these international restrictions and their administration by an international organization, Iran’s exports have been heavily influenced. Iran’s crude oil exports have dropped from 2.5 million barrels per day in 2011 to 1.1 barrels in 2013. Accordingly, Iran’s economy has declined by 5 percent in 2013 due to the limitations imposed on the private sector (Katzman, 2015).

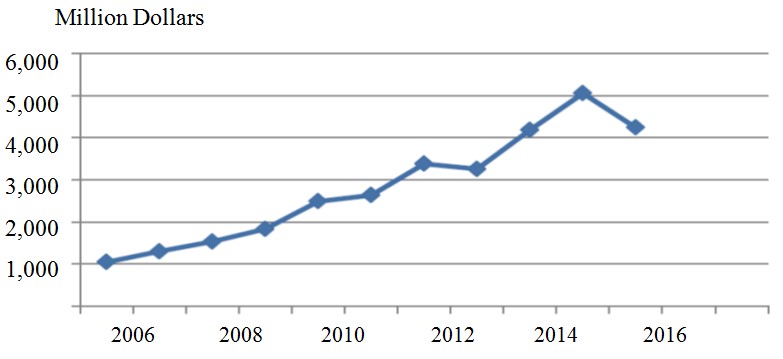

Despite the sanctions selectively imposed by Western countries, a number of stable companies with carefully thought out planning and solidarity have experienced a different situation as “Figure 1”.

Conducting a risk assessment to identify existing and emerging risks both internally and externally, and then prioritizing and managing these risks are effective solutions while working with export control and sanctions compliance (Gorrissen Federspiel, 2015).

Nafis Nakh Public Joint Stock Company with committed and educated management staff has been able to manage strict sanctions conditions using the aforementioned solutions. This successful textile company has focused on the production of a wide range of high quality products to assure the quality of textile mills fabrics and other downstream industries.

This has been possible with the employment of the latest management techniques and highly flexible and dynamic organizational systems. As a result, the company’s exports have increased sharply in recent years.

Therefore, Nafis Nakh Co is selected to investigate what affects the export performance and the propensity to export.

2. Literature Review

Tendency of firms to export and ceaselessly service overseas markets are often associated with internal and external factors. Internal factors include the demographic and management characteristics of the company while external factors comprised of industry features, government support and foreign market forces (Bilkey, 1978; Cavusgil and Nevin, 1981; Zou and Stan, 1998; Leonidou et al., 2002; O’ Cass and Julian, 2003).

In International Business studies, several literature reviews indicated the most frequently cited variables used to explain export performance. Moini (1995) suggested three broad classes: organizational characteristics (size, international experience, competitive advantages, etc.); managers’ expectations (both positive and negative); and managers’ characteristics (age, formal education, experience, knowledge of foreign languages); while adding a fourth factor, systematic search for new external markets.

Leonidou, Katsikeas and Samiee (2002) found that the impact on export performance varied according to the specific facet or measure of export performance selected, and that five types of variables seemed to dominate most of the studies: managers’ characteristics, organizational factors, environmental forces, export target, and export marketing strategy.

Caparas (2006) examined the determinants of export performance of the Philippine manufacturing sector. Their study indicated both a positive linear and negative non-linear relationship between firm size and export performance as measured by export sales to total sales for the Philippine clothing sector, but the results were not statistically significant in the food processing and electronics sectors.

Sera, Pointon and Abdou (2012) examined which particular organizational and managerial factors contribute to the propensity to export in a sample of 167 Portuguese and 165 UK firms in the textile and clothing industry. According to their findings, For Portugal, the size of firm and the educational level of managers are the key determinants of export propensity. As to the UK, age and perception of costs are the key factors.

Love, Roper and Zhou (2016) identified separately the positive effects on exporting from the international experience of the firm and the negative effects of firm age using a survey of internationally engaged UK SMEs. They also found that Innovation has positive exporting effects with more radical new-to-the-industry innovation most strongly linked to inter-regional exports while they found no evidence, relating early internationalization to extra-regional exporting.

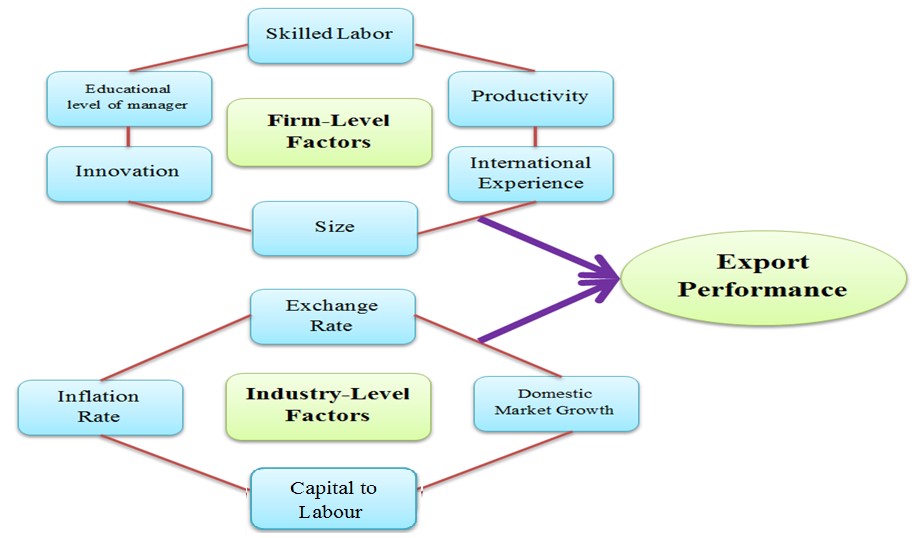

In general, the literature review indicated several factors related to the firm-level and industry-level that are potentially able to affect the export decisions and enterprises’ export performances.

In the present study, most frequently cited variables used to explain export performance are as follows:

- Firm-level factor includes:

firm size, international experience, productivity, educational level of managers, skilled labor and innovation. - Industry-level factor includes:

exchange rate volatility, inflation rate, capital to labour ratio and domestic market growth.

3. Methodology

Our analysis is based on data from Nafis Nakh, a successful and growth textile company in terms of export. The study analyses firm’s resources and capabilities in a ten year period from 2007 to 2017 using monthly time series data.

3.1. Variable Construction and Calculation

3.1.1. Firm Size

Big firm size reflects a better profit accomplishment in the future. Large companies have more financial resources as well as more production capacity for export (Bonaccorsi, 1992). A large number of empirical studies found that firm size, has a linearly significant and positive effect on a firm’s export performance (Jongwanich and Kohpaiboon, 2008). The proxy of firm size is measured by book value of total assets. Because of the huge amount of firm assets’ value, it is calculated in million rupiahs and is changed into natural logarithm (Ln) (Setiadharma and Machali, 2017).

Firm Size = Ln Total Assets at time (t) (1)

3.1.2. International Experience

International Experience, indicating a learning-by-doing experience, can also significantly affect firm export performance, since more experienced companies firms are able to participate in competitive foreign markets due to their cumulative experience, business networks and reputation. They will suffer less risk due to international experience (Kokko et al., 2001).

In the present study this factor computed as follows:

Firm Experience = The months of activity in the international market at time (t) (2)

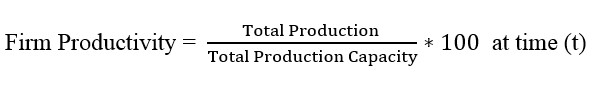

3.1.3. Productivity

Firms can export after improving their technologies and production processes, making new investments to improve their efficiency, training their work force, and using external auditing. A series of these decisions, therefore, raise their productivity (Driemeier et al., 2002). Strong evidence indicates that only more efficient firms can participate in the export market (Cherides et al., 1996). Total productivity of firm is defined as follows:

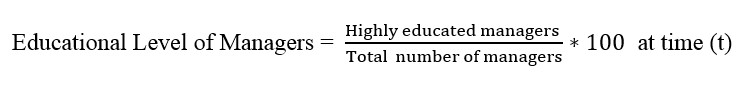

3.1.4. Educational Level of Managers

The international new ventures literature takes a broader view of the available internal and external knowledge sources for internationalization, including the prior international experience of management, knowledge obtained from hiring internationally experienced managers (Fletcher and Harris, 2012). This factor, reflecting educational level of managers is measured using the formula:

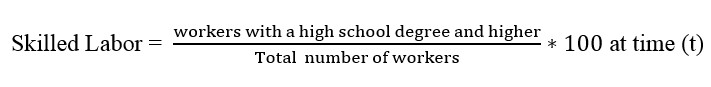

3.1.5. Skilled Labor

Higher skilled labor is associated with higher labor productivity which will affect a firm’s export performance. A large number of empirical studies found that more highly skilled workforces, especially more graduate employees, were likely to become more successful in export markets (Roper and Love, 2002).This factor is measured as follows:

3.1.6. Innovation

One of the key attributes which allows firms to enter new markets is having new, competitive products which can help overcome domestic competition in foreign markets. Innovation can do so by upgrading product quality or by providing customized products which are developed specifically for foreign markets (Rodriguez & Rodrıguez, 2005).

In the present study, following Papadogonas et al, (2007), R&D expenditure is considered as an indicator of innovation measurement as follows:

Innovation = Ln Total R&D expenditures at time (t) (6)

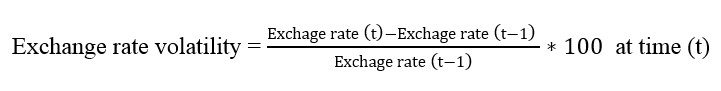

3.1.7. Exchange rate volatility

An exchange rate is the price of a nation’s currency in terms of another currency. Exchange rate volatility can be defined as exchange rate movements that emanate from currency fluctuations. It is a generally held view that exchange rate fluctuations are an important source of macroeconomics uncertainty and thus have a significant impact on firm value.

This is because growing globalization has encouraged many corporations to benefit from competitive advantage and economies of scale in global market (Afza and Alam, 2014). This factor computed as follows:

In this study, the data related to this factor was produced and published by Central Bank of Iran.

3.1.8. Inflation rate

A large number of empirical studies confirmed the significant impact of inflation on exports (Gylfason, 1999). Inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising and consequently, the purchasing power of currency is falling.

inflation is inversely correlated with real exchange rates as long as nominal exchange rates do not adjust instantaneously to prices even if high inflation may impede exports and growth through other channels as well (Dexter et al., 2005). In the present study, the statistics published by Central Bank Of Iran are used To calculate this factor.

3.1.8. Capital to Labour ratio

The Capital to Labour ratio measures the ratio of capital employed to labor employed. It captures the characteristics of an industry and also the country’s comparative advantage, especially in developing nations in which labour is relatively cheap compared with capital.

A lower capital- labour ratio in an industry, therefore, indicates that firms, which produce labor-intensive products, are likely to compete with foreign firms in the international market due to their cheap labour supply aligned with the country’s comparative advantage (Jongwanich and Kohpaiboon, 2008).

However, as a contradiction over time, firms tend to have a higher capital-labour ratio as they seek to gain productivity improvement from investment in automating the production process (Pettinger, 2017). This factor is measured as follows:

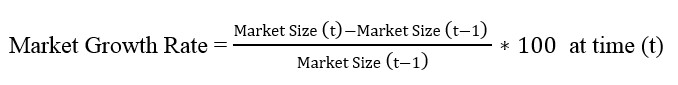

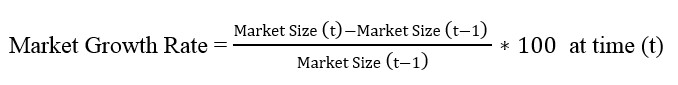

3.1.9. Domestic Market Growth rate

The domestic market conditions can lead companies to foreign markets (Buckley, 1990). Market Growth rate is defined as the rise in sales or “market size” within a given customer base over a specific period of time. The market size is defined through the market volume and the market potential.

The market volume exhibits the totality of all realized sales volume of a special industry in a special market. Qualitative measuring mostly uses the sales turnover

as an indicator of growth in local markets (Aaker and Mcloughlin, 2010). Domestic Market Growth rate is defined as follows:

The statistics published by Tehran Stock Exchange have been used in order to calculate the amount of monthly sales in the textile industry during the research period.

3.2. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

As it was mentioned, in this paper effort was made to examine what affects the export performance and the propensity to export. In order to evaluate the impact of most frequently cited variables in both firm-level and industry-level on export performance; conceptual model and hypotheses of the study were developed as “Figure 2”.

Research hypotheses about the influence of each of the ten preliminary explanatory factors over the export performance are tested in two groups as follows:

Group One (Firm-Level factors):

H1. Firms’ size has a positive impact on export performance.

H2. International experience has a positive impact on export performance.

H3. Productivity has a positive impact on export performance.

H4. Educational level of managers has a positive impact on export performance.

H5. Skilled Labor has a positive impact on export performance.

H6. Innovation has a positive impact on export performance.

Group Two (Industry-Level factors):

H7. Exchange rate volatility is negatively associated with export performance.

H8. Inflation rate is positively associated with export performance.

H9. Capital to Labour ratio is negatively associated with export performance.

H10. Domestic market growth rate is positively associated with export performance.

3.3. Data and Estimation

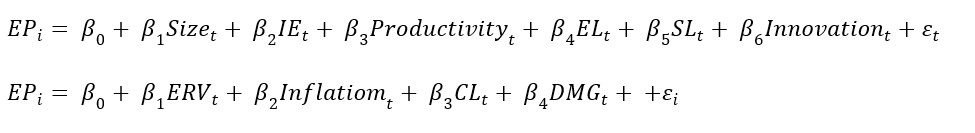

The hypothesis presented in the previous section will be tested in times series data of Nafis Nakh Co, for the period of 2007-2017. To assess what affects firm’s export performance, in both firm-level and industry-level, we estimate the following regressions:

Where EPt as the Dependent variable, denotes firm’s exporting performance at month (t). In the present study, export value of the firm is used as an indicator of export performance that was calculated in million and is changed into natural logarithm.

Applying the method of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with variables where their values are bounded between zero and one will lead to biased and inconsistent estimators (Kumbhakar and Lovell, 2000). Therefore, in this study, no variable take such values and even fractions such as growth rates calculated as numbers as mentioned in the “Variable Construction and Calculation” section.

Other variables in the model including independent variables are: Size the size of the firm; IE denotes the international experience of the firm; Productivity firm’s productivity; El denotes the educational level of managers; SL denotes the skilled labor; Innovation firm’s innovation and ε is the random errors of the regression models.

In the equation (2), EVR denotes the exchange rate volatility, Inflation the inflation rate of the country; CL denotes the market capital to labour ratio and DMG is the domestic market growth rate.

Our analysis is based on data from firm’s internal information especially its financial statements and the statistics produced and published by Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE) and Central bank of Iran.

4. EMPIRICAL RESULTS

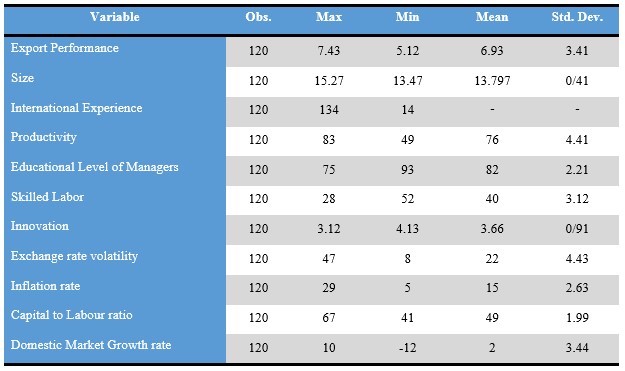

This paper investigates the impact of several firm-level and industry-level factors that are potentially able to affect the export decisions and enterprises’ export performances. In this section, we examine the impact of each factor on firm economic performance through testing the research hypotheses.

Two econometric models were identified, which aim to test the effects of significant firm-level and industry-level factors on the firm’s export performance. The use of these estimation techniques is aimed at increasing the confidence of the empirical results as illustrated in Tables (2) and (3).

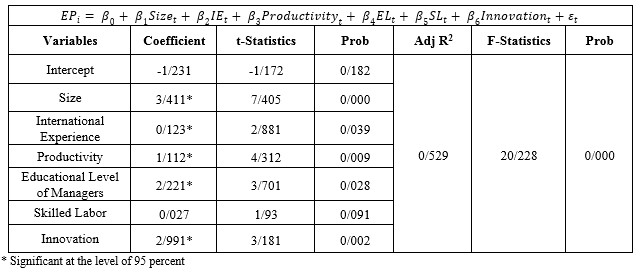

Table (2) contains the OLS regression estimates of equation (10).

Six hypotheses were supported Table (2). The results appear economically significant according to Adj R2, F-Statistics and Prob statistics.

Firm Size: the coefficient of size, β1, is significant and positive, reflecting that higher firm size is correlated with higher export performance. Thus, the first hypothesis of research is confirmed.

International Experience: the coefficient of international experience, β2, is significant and positive, reflecting that higher international experience is correlated with higher export performance.

Productivity: the coefficient of productivity, β3, is significant and positive; reflecting that higher productivity is correlated with higher export performance, the third hypothesis of research is confirmed.

Innovation: the coefficient of innovation, β6, is significant and positive, reflecting that higher innovation is correlated with higher export performance. Thus, hypothesis no.6 of research is confirmed.

The Educational Level of Managers and Skilled Labor coefficient take a P-value of 0/481 and 0/091 reflecting that these factors have no significant effect on export performance (hypothesis no.4 and no.5 are rejected).

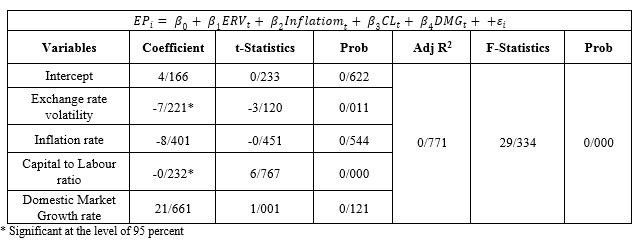

Four hypotheses were tested through Estimation results reported in Table (3). The results appear economically significant according to Adj R2, F-Statistics and Prob statistics.

Exchange rate volatility The coefficient of exchange rate volatility, β1, is significant and negative, reflecting that exchange rate volatility is negatively correlated with higher export performance, the hypothesis no.7 of research is confirmed.

Capital to Labour ratio: the coefficient of Capital to Labour ratio, β3, is significant and negative, reflecting that exchange rate volatility is negatively correlated with higher export performance, the hypothesis no.9 of research is confirmed.

The Inflation Rate and Domestic Market Growth rate: the coefficient take a P-value of 0/544 and 0/121, reflecting that in the present study, we found no evidence that these factors have any significant effect on export performance (hypothesis no.8 and no.10 are rejected).

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Since exports can improve a firm’s production efficiency to overcome higher trade barriers and address different market tastes in competitive international markets, the ability of firms to internationalize has received significant research attention.

In the present study, effort was made to investigate what affects the export performance. The explanatory model with variables from two main areas of influence – firm level and industry level – was fit to ten years monthly time series data from Nafis Nakh Textile Company.

Two equations were employed by a series of estimation techniques in order to evaluate the impact of each firm-level and industry-level factors on export performance. Finally ten empirical results were identified through testing the research hypothesis.

First, for the firm size, it was found to be statistically and positively related to a firm’s export performance. This result strongly implies that large firms are likely to participate in the international market, since they can cover sunk costs necessary to enter into export markets. In other words, large firms can earn sufficient profits to cover their sunk costs incurred during exporting.

This empirical evidence is consistent with the findings of Caparas (2006) and Jongwanich & Kohpaiboon (2008).

Although young firms are more proactive, flexible, and aggressive than older firms, as expected, positive significant effect of international experience on export performance was found. It implies that firms with more experience tend be more efficient through their learning-by-doing process and thus can compete with foreign companies due to their cumulative experience. The result is consistent with the findings of D’Angelo et al, (2013) and Gallego & Casillas (2014).

Significant and positive effects of firm’s productivity on export performance were found which confirms that the most productive firms can survive in highly competitive foreign markets, resulting in a higher level of export performance. The reason is that there exist additional costs in exporting to foreign countries. The result is consistent with the results of Jongwanich and Kohpaiboon (2008).

The empirical findings, relating to Educational level of managers point to the positive significant effects of this important factor on export performance. Lack of managerial knowledge about international markets is often cited by firms as one of the main barriers to exporting and internationalization.

Recruitment of managers with international or export experience represents a direct injection of international understanding into the firm and is likely ceteris paribus to increase the extent of internationalization. The results confirm that highly educated Management team helps firms overcome the difficulties and uncertainties of going international. The findings are consistent with the results of Serra et al, (2012) and Love et al, (2016).

As expected, the results imply that there is a strong positive association between innovation and export performance confirming that innovation and exporting work jointly to improve performance. The reason for this complementarity links back to the issue of organizational learning and knowledge acquisition.

R&D expenditures help firms generate new and improved products, which in turn enable entry to further export markets. This significant result for innovation is consistent with the findings of Salomon & Jin, (2010), Rodriguez & Rodriguez, (2005) and D’Angelo et al, (2013).

In order to investigate the factors related to the industry-level, a strong negative association between exchange rate volatility and export performance was found as it was expected. Logically, with the devaluation of the national currency, firms’ willingness to export is rampant and firms to try to allocate all or part of their sales to foreign

markets in such situation. The result is consistent with the findings of many studies such as Viera (2016), Chit (2008) and Srinivasan & Kalaivani (2013).

Capital to Labour ratio was also found to be significantly and negatively related to firm’s export performance. This result confirms that an industry with a low capital – labour ratio tends to participate in foreign markets, since it competes with foreign firms by supplying cheap labour-intensive products, especially in developing nations like Iran in which labour is relatively cheap compared with capital.

This significant and negative association between firm’s export performance and the industry’s Capital to Labour ratio is consistent with the result of Jongwanich & Kohpaiboon (2008) and Forslid & Okubo (2011).

Finally we found no evidence that there is any significant relationship between export performance and the other three factors that seemed to have significant effects include skilled labor, inflation rate and domestic market growth.

This study has also confirmed some results found in the literature, while the developing country setting contributed to the external generalizability of past findings. Practitioners may reap some benefits from the normative orientation that can be drawn from the results.

Future research should continue the quest for a better measure of export performance and the systematic replication of some agreed-upon measuring instrument should allow easier comparison between the results of different studies.

Also, the effects of explanatory factors on other facets of export performance (e.g., market performance, strategic performance) should be investigated. Contingencial models and mediating effects should also be evaluated.

International experience may also have diversity and intensity dimensions, suggesting that firms with experience of more diverse international markets or more intensive engagement with international markets may experience stronger organizational learning. Future studies might seek to address these alternative dimensions of international experience.

References

[1] Aakar, D., Mcloughlin, D. (2010). Strategic Market Management-Global Perspectives. West Sussex, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

[2] Adjasi, C. (2007), Are exporting firms really productive? Evidence from Ghana. Internationalization and economic growth strategies in Ghana: A business perspective, London: Adonis and Abbey: 73-92.

[3] Afza, M., Alam, K. (2014). Managing foreign exchange risk among Ghanaian firms, Journal of Risk Finance, 6(4): 306-318.

[4] Amornkitvikai, Y., Harvie, C & Charoenrat, T. (2012). Factors affecting the export participation and performance of Thai manufacturing small and medium sized Enterprises (SMEs). 57th International Council for Small Business World Conference, Wellington, New Zealand: International Council for Small Business: 1-35.

[5] Bilkey, W. (1978). An attempted integration of the literature on the export behavior of firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 9(2): 33-46.

[6] Bonaccorsi, A. (1992). The Relationship between Firm Size and Export Intensity. Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 23(4): 605-35.

[7] Buckley, P. (1990). Problems and development in the core theory of international business. Journal of International Business Studies, (4): 567-664.

[8] Caparas, D. (2006), Determinants of Export Performance in the Philippine Manufacturing Sector. Discussion Paper Series No, Makati City, Philippines.

[9] Cavusgil, S., Nevin, J. (1981). International determinant of export marketing behavior: an empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1): 114-119.

[10] Chit, m. (2008). Exchange rate volatility and exports: evidence from the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 6(3): 241-259.

[11] D’Angelo, A., Majocchi, A., Zucchella, A & Buck, T. (2013). Geographical pathways for SME internationalization: Insights from an Italian sample. International Marketing Review, (30): 80–105.

[12] Dexter, A., Levi, M & Nault, B. (2005). International Trade and the Connection between Excess Demand and Inflation. Review of International Economics, 13(4): 699-708.

[13] Dizaji, S., Van Bergeijk, P. (2013). Potential Early Phase Success and Ultimate Failure of Economic Sanctions: a VAR Approach with an Application to Iran. Journal of Peace Research, 50(6): 721–736.

[14] Fernandez, S., Laird, S & Vanzetti, D. (2004). Market Access Proposals for Non-Agricultural Products. UNCTAD Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities.

[15] Fletcher, M., & Harris, S. (2012). Knowledge acquisition for the internationalization of the smaller firm: Content and sources. International Business Review, (21): 631–647.

[16] Forslid, R., Okubo, T. (2011). Are Capital Intensive Firms the Biggest Exporters?. The research institute of economy, Trade and Industry, Discussion Paper Series 11-E-014.

[17] Gallego, A., Casillas, J. (2014). Choice of markets for initial export activities: Differences between early and late exporters. International Business Review, (23): 1021–1033.

[18] Gylfason, T. (1999). Export, Inflation and Growth. World development Journal, 27(6): 1031 –1057.

[19] Hallward, Driemeier., Iarossi, G & Sokoloff, k. (2002). Exports and Manufacturing Productivity in East Asia: A Comparative Analysis with Firm-Level Data, NBER Working Papers 8894, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

[20] James, H., Love, A., Roper, S & Zhou, Y. (2016). Experience, age and exporting performance in UK SMEs, International Business Review, (25): 806–819.

[21] Jongwanich, J., Kohpaiboon, A. (2008). Export Performance, Foreign Ownership, and Trade Policy Regime: Evidence from Thai Manufacturing. ADB Economics Working Paper No.140, Asian Development Bank, Metro Manila, Philippines.

[22] Katzman, K. (2015). Iran Sanctions. Congressional Research Service, RS20871.

[23] Kokko, A., Zejan, M & Tansini, R. (2001). Trade Regimes and Spillover Effects of FDI: Evidence from Uruguay’. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, (137): 124–149.

[24] Kumbhakar Subal, C., Lovell, C. (2000). Stochastic Frontier Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

[25] Leonidou, L., Katsikeas, S & Samiee, S. (2002). Marketing strategy determinants of export performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 55(1): 517-567.

[26] Moini, A. (1995). An inquiry into successful exporting: an empirical investigation using a three-stage model. Journal of Small Business Management, 33(3): 9-25.

[27] O’ Cass, A., Julian, C. (2003). Examining firm and environment influence on export marketing mix strategy and export performance of Australian exporters. European Journal of Marketing, 37 (3/4): 336-384.

[28] Papadogonas, T., Fotini, V & Agiomirgianakis, G. (2007). Determinants of export behavior in the Greek manufacturing sector. Operational Research, 7(1): 121-135.

[29] Pettinger, T. (2017). Human Capital definition and importance, Economics help website.

[30] Rodriguez, J., Rodriguez, R. (2005). Technology and export behavior: A resource based view approach. International Business Review, (14): 539–557.

[31] Roper, S., Love, H. (2002). The Determinants of Export Performance Panel Data Evidence from Irish Manufacturing Plant.RP02024, Aston University, Aston Business School Research Institute, Birmingham, UK.

Salomon, R., Jin, B. (2010). Do leading or lagging firms learn more fromexporting? Strategic Management Journal, (31): 1088–1113.

[32] Serraa, F., Pointonb1, J & Abdouc., H. (2012). Factors influencing the propensity to export: A study of UK and Portuguese textile firms. International Business Review, 21(2): 210-224.

[33] Setiadharma, S., Machali, M. (2017). The Effect of Asset Structure and Firm Size on Firm Value with Capital Structure as Intervening Variable. Journal of Business & Financial Affairs, 6(4): 1-5.

[34] Srinivasan, P., Kalaivani, M. (2013). Exchange rate volatility and export growth in India: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Growing science, 2(3): 191-202.

[35] Viera, F. (2016). Exchange rate volatility and exports: a panel data analysis. Journal of Economic Studies, 43(2): 2013-221.

[36] Zou, S., Stan, S. (1998). The determinants of export performance: a review of the empirical literature between 1987 and 1997”. Journal of International Marketing Review, 15(5): 333-350.

No comment